高胆固醇血症:何时干预最合适?

年日本

根据动脉粥样硬化的病理改变,推测予以更早期的血脂干预可能会更进一步获益。但动脉粥样硬化是多因素疾病,高血压、糖尿病、吸烟等均是重要因素,且目前的临床研究所得获益数值均是相对值,因而早期干预不一定能得到人们期望的良好结果。基因学方面,目前的药物治疗靶点多在血脂的生成和转运,与PCSK9的调控有所不同,PCSK9基因研究的结果是否适用于早期干预仍未知。此外,有研究提示基因表达下调LDL水平的获益要优于药物干预的LDL水平下降。因为缺乏充分的循证医学证据,早期干预的获益是否如期望的那样显著尚不明确。

早期干预时存在的另一个问题是胆固醇控制在何水平最佳?目前,冠心病二级预防的血脂控制水平仍有一定的争议,是否越低越好?对于缺乏临床试验的早期干预更是如此。因而在早期干预时达到什么要的治疗目标尚不明确,给临床实际应用带来困扰。

2.3 可行性

由于成本-效益的要求,对于低风险的患者行调脂治疗需考虑医疗成本和临床获益的关系。一项研究显示,若要对35岁以上人群进行调脂治疗(LDL大于130mg/dl),为保证预期成本-效益,他汀类药物的价格要低于0.1美元。由于价格因素和临床获益的不确定性,可能会导致成本的大大增加,降低可行性。

早期干预意味着患者长期服用药物,并且药物的疗效无法直观观察到,依从性存在较大的问题,尤其是年轻患者;同时长期服药可能会对患者产生影响,引起额外的精神负担,进而影响生活质量,产生新的问题。

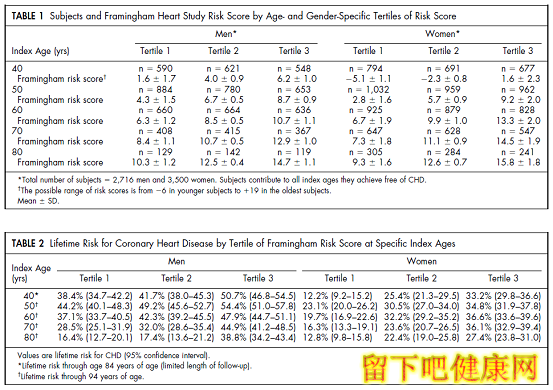

图2 不同年龄、性别的10年和终生冠心病风险 上图中表1是该研究入选人群年龄、性别分层的弗雷明汉10年风险积分,表2是冠心病终生风险积分;Tertiles是风险积分的分层,以40岁为例,男性10年冠心病风险在Tertiles1, 2, 3组分别为0%, 2.2%和11.6%,女性分别为0%, 0.7%和2.3%

3 何时干预最合适?

因为存在上述的问题,目前尚不能也无需对所有人群进行干预。有学者提出冠心病终生风险的概念来选择合适的人群,Lloyd-Jones等的研究来源于Framingham队列数据的分析,如胆固醇水平在200~239mg/dl的40岁男性,其10年冠心病风险仅为5%,但其终生风险可达43%。综合分析多种因素,对30岁以上、终生风险大于40%的患者开始干预是合适的。有关不同年龄和性别的10年和终生冠心病风险见图2(引自),可根据冠心病终生风险的大小,选择干预的时机。尽管如此,在临床实际应用中,仍需根据患者临床特点实施个体化医疗,不可一概而论。

高胆固醇血症时冠心病的重要危险因素,病理学、基因学和相关临床研究均提示早期干预可能会更进一步获益,但长期服用的安全性和有效性仍需进一步明确。临床应用时,需根据患者临床情况实施个体化医疗。

参考文献

1. Grundy SM. United States Cholesterol Guidelines 2001: expanded scope of intensive low-density lipoprotein-lowering therapy. Am J Cardiol. 2001;88:23J–27J.

2. Baigent C, Keech A, Kearney PM, Blackwell L, Buck G, Pollicino C, Kirby A, Sourjina T, Peto R, Collins R, Simes R. Efficacy and safety of cholesterol-lowering treatment: prospective meta-analysis of data from 90,056 participants in 14 randomised trials of statins. Lancet. 2005;366:1267–1278.

3. O’Keefe JH Jr, Cordain L, Harris WH, et al. Optimal low-density lipoprotein is 50 to 70 mg/dl: lower is better and physiologically normal. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43:2142–2146.

4. Cannon CP, Braunwald E, McCabe CH, et al. Intensive versus moderate lipid lowering with statins after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med.2004;350:1495–1504.

5. Steinberg D. Earlier intervention in the management of hypercholesterolemia: what are we waiting for? J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56(8):627-629.

6. Tuzcu EM, Kapadia SR, et al. High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation. 2001;103:2705–2710.

7. Tuzcu EM, Kapadia SR, Tutar E, et al. High prevalence of coronary atherosclerosis in asymptomatic teenagers and young adults: evidence from intravascular ultrasound. Circulation 2001;103:2705–10.

8. Cohen JC, Boerwinkle E, Mosley TH Jr, et al. Sequence variations in PCSK9, low LDL, and protection against coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med 2006;354:1264 –72.

9. Brown MS, Goldstein JL. Biomedicine: lowering LDL: not only how low, but how long? Science. 2006;311:1721–1723.

10. McPherson R, Kavaslar N. Statins for primary prevention of coronaryartery disease. Lancet. 2007;369:1078.

11. Benn M, Nordestgaard BG, Grande P, et al. PCSK9 R46L, low-density lipoprotein cholesterol levels, and risk of ischemic heart disease: 3 independent studies and meta-analyses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;55:2833-2842.

12. Prevalence of small vessel and large vessel disease in diabetic patients from 14 centres: the World Health Organisation Multinational Study of Vascular Disease in Diabetics: Diabetes Drafting Group. Diabetologia.1985;28(suppl):615– 640.

13. Robertson TL, Kato H, Rhoads GG , et al. Epidemiologic studies of coronary heart disease and stroke in Japanese men living in Japan, Hawaii and California: incidence of myocardial infarction and death from coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 1977; 39:239 –243.

14. Wiegman A, Hutten BA, de Groot E, et al. Efficacy and safety of statin therapy in children with familial hypercholesterolemia: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2004;292:331–337.

15. Pletcher MJ, Lazar L, Bibbins-Domingo K, et al. Comparing impact and cost-effectiveness of primary prevention strategies for lipidlowering.Ann Intern Med. 2009;150:243–54.

16. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wilson PW, Larson MG, et al. Lifetime risk of coronary heart disease by cholesterol levels at selected ages. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163: 1966–1972.

17. Lloyd-Jones DM, Wilson PW, Larson MG, et al. Framingham risk score and prediction of lifetime risk for coronary heart disease. Am J Cardiol. 2004;94:20-24.